Cold, Flu … and COVID Season

What if we shift focus from battling COVID to a more efficient strategy—mitigating COVID, flu, and other respiratory diseases together?

We have powerful tools—including vaccines, antiviral treatments, and nonpharmaceutical interventions like masking—to control SARS-CoV-2. These tools not only make it possible to move on and live with COVID but have the potential to prevent many other respiratory illnesses.

In this Q&A, adapted from the February 18 episode of Public Health On Call, infectious disease physician Celine Gounder, MD, ScM ’00, talks with Joshua Sharfstein, MD, about shifting focus in 2022 away from COVID alone to a set of respiratory pathogens including SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and RSV.

Why may 2022 look different than 2021?

I think we are in a very different place now in February 2022 than we were early in the pandemic or even a year ago. We have multiple highly effective and safe vaccines. About two-thirds of the population in the U.S. has now been fully vaccinated. We're seeing the benefits of that translated into [reduced] rates of hospitalization and death. Most people who end up in the hospital and die from COVID are still not yet vaccinated.

We have come to realize the SARS-CoV-2 virus cannot be eradicated or eliminated. For the foreseeable future—in our lifetime, our children's lifetime, and our grandchildren's lifetime—COVID is going to be part of life. We have some great tools—especially but not only the vaccines—to control SARS-CoV-2. It'll be like other common coughs, cold, and flu viruses that we deal with, and will probably be the worst one. But it is something that we're going to have to figure out how to cope with.

Recently, you have been laying out what coping with COVID looks like and the idea that COVID should be grouped with other respiratory diseases. What do you mean by that?

There are a number of viral respiratory infections that have similar modes of transmission for which similar mitigation measures will also have an impact. By mitigating SARS-CoV-2, we can also have a tremendous impact on other important other respiratory viral infections, including influenza and RSV [respiratory syncytial virus]. Both cause significant disease and even death in some cases, particularly in the elderly, as well as in younger children.

Before COVID, in bad influenza and RSV years, we would see something like 35,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths per week.

We also know that influenza and RSV can trigger flare-ups of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which includes emphysema. You can prevent not just COVID, but a significant amount of lung disease by tackling these [viruses] together.

These viruses affect people in similar ways. Are they also similar in how they're transmitted and can be prevented?

Yes. SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV, as well as other viral respiratory infections are similarly transmitted, either airborne, aerosolized, or in some cases also droplet-borne. Many of the measures that we use to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 also prevent transmission of these other viral respiratory infections. In fact, we've seen over the last two years that we've really crushed the curve on influenza, on the flu, through the very same measures we use to control COVID.

What are the implications of thinking of these diseases together?

I think it impacts how you think of the array of interventions and how you assess their effectiveness. Many of these different measures will be familiar to people. For example, masking, indoor air ventilation and filtration—these are measures that will control COVID as well as influenza and RSV.

How might that impact you and your personal life? Well, just as the weather report will say, “Today it's going to rain,” and you take an umbrella with you, maybe the weather report includes, “It's cough, cold, flu, and COVID season and there's a lot of transmission. This is the time of year to wear a mask in the winter.”

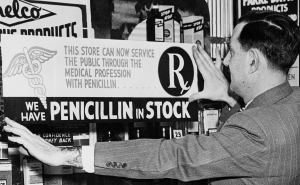

Another measure that we use to prevent COVID is vaccination. We also use it to prevent influenza. [We should try] to pair our efforts to get people vaccinated ahead of the cold, flu, and COVID season.

Then you also have, recently, the scale-up of rapid antigen home tests for COVID. They also exist for the flu; we just haven't been using them over the counter. We've been using them in the ER, in clinics, or in the hospital.

Just like with COVID, where we now have new antiviral pills—namely Pfizer's Paxlovid drug and Merck's molnupiravir—we for a long time have had oral medications for the flu. Unfortunately, very often they are not taken in time to have an impact on the course of disease because the diagnosis is made too late, the prescription is given too late, the person started treatment too late. [We need] to think of these sorts of things in tandem with “it's cough, cold, flu, COVID season. I need to get a test for COVID and the flu.”

If people test positive for either, we need to have an expedited process for them to access free medications.

Public Health On Call

This article was adapted from the February 18 episode of Public Health On Call Podcast.

What does this do to our data dashboard? Will we still have the COVID dashboard, or does it look different?

Our data on COVID is a lot better than it is for influenza and RSV, not to mention the many other viral respiratory infections.

I think part of what would need to happen would be better surveillance for all of them—which would also help us be better prepared for the next pandemic. We've always thought the flu would be the cause of the next big, scary pandemic. I think bringing along surveillance on these other viral respiratory infections with what we're doing for COVID will strengthen our preparedness.

I can appreciate the potential value of looking at these infections together. But there are also important differences between them. For example, the evidence seems to support that influenza is much more easily transmitted among children than SARS-CoV-2 is. How do those differences play out in a respiratory disease strategy?

In addition to schools, a place where you would have differences is in hospitals. Length of hospitalization for influenza, versus RSV, versus COVID is not going to be the same. I think you still want to collect data on each of them individually; the resource allocation with a hospitalization is going to be different.

If you want to model or predict your workforce capacity and hospital bed needs, you need that level of data. At the same time, the interventions we're using to prevent influenza, RSV, and COVID are essentially the same—with the exception of the vaccines and the drugs that we use to treat these infections. All the other mitigation measures are the same.

Do you really need to worry about distinguishing influenza versus COVID in deciding whether to recommend masks at certain times of year, or to upgrade your HVAC systems? What really matters at the end of the day is: are people getting sick? Are they ending up in the hospital? Are hospitals getting crushed by that overload? And are people dying?

So, the future may look a little bit different. We're not going to be as obsessed with COVID, but we may be tracking respiratory disease in a way we didn't prior to the pandemic, and taking action to protect ourselves based on the big picture.

Yes. If we decide to take indoor air quality as seriously in the 21st century as we did, for example, water quality in the 20th century, I think we may have a tremendous impact on any number of viral respiratory infections.

Presumably, we'd also be in a better position if new respiratory diseases pop up.

That's the beauty of having this more holistic approach. This is a mindset, a strategy, that will shield us from other respiratory infections—[including] some that have not yet emerged. Having strategies that are targeted at individual viruses is much more difficult and costly, and [takes] much more effort than figuring out the highest-yield interventions that can make an impact across the board.

Joshua Sharfstein, MD, is the vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement and a professor in Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is also the director of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and a host of the Public Health On Call podcast.