What to Know About MMR and MMRV Vaccines

What’s in these vaccines, why are they combined, and are they safe?

*Editors’ note: This article was updated on October 7, 2025, to include additional information about combined vaccines.

For decades, vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella—or chickenpox—have been a standard part of American kids’ vaccination schedules. Children in the U.S. are vaccinated against these diseases twice—first at 12–15 months old, and then at 4–6 years old.

The combination measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) has been in use since 1971. In 2005—after clinical trials showed that it was safe and effective to do so—parents were given the option to choose a combination MMRV vaccine that also includes varicella, in large part to reduce the number of injections a toddler receives at their doctor’s visit.

Since 2009, however, the CDC has recommended that kids under age 4 receive the MMR and varicella shots separately. The agency made the change after post-licensure monitoring—which tracks rare adverse events once vaccines are widely used—revealed the small risk of febrile seizures following the first dose of the vaccine. These seizures are linked to fever and cause no long-term harm or risk of recurrence.

About 1 in every 1,500–2,000 first doses of the MMRV vaccine result in febrile seizures in the one to two weeks after vaccination; the seizure risk after the second dose, given between ages 4 and 6, is “almost non-existent,” says William Moss, MD, MPH, a professor in Epidemiology and executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center.

The CDC has long been aware of that risk but has maintained the MMRV option for younger kids whose parents feel strongly and are made aware of the possible side effects, says Moss.

“This is an issue that has been thoroughly investigated, discussed, [and] reviewed multiple times by ACIP,” the committee that advises the CDC about how vaccines are used in the U.S., says Moss.

Benefits of Combining MMR and Varicella Vaccines

The MMR and varicella shots were considered good candidates to be combined because they are delivered on the same vaccine schedule and are made by the same manufacturer—Merck—explains Moss.

“Combination vaccines are rigorously studied in clinical trials” to ensure they don’t reduce the effectiveness of any component or impact the vaccine’s safety, Moss says.

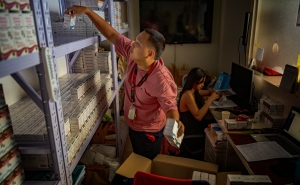

They have numerous benefits for public health and for patients, reducing the number of injections a child receives and the costs associated with vaccine visits for patients and providers. For providers, it cuts back on cold storage space for the shots, which have to be refrigerated.

The Proposal to Separate MMR and Varicella Vaccines

In September, ACIP voted 8–3 to recommend that kids under 4 receive the MMR and varicella vaccines separately due to the slightly higher risk of febrile seizures in young toddlers after the first dose.

If adopted by the CDC, the recommendation will change little for most families—85% of U.S. parents already opt for separate vaccines for that first dose of MMR and varicella, which can be given at the same time with no increased risk of seizure. This is likely because the concentration of varicella virus is higher in the combination vaccine than in the varicella-only vaccine.

But in essence, the recommendation would “take away parental choice” about whether to take combined or separate shots, says Moss.

The Trump administration has also called for the MMR vaccine to be broken out into three separate shots, and urged pharmaceutical companies to develop these monovalent measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines, which aren’t currently available in the U.S.

Doing so would “falsely imply that there is something unsafe about giving the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the same time,” Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told USA Today.

“And if you break them apart, there’s a much higher likelihood that a child’s going to miss one or two” vaccinations, says Moss.

MMR and MMRV Vaccine Formulas and Side Effects

The MMR and MMRV vaccines contain live weakened, also known as live-attenuated, versions of the viruses they protect against—inducing an immune response without causing disease.

“You want that immune response,” says Moss. “It trains the immune system so when you see the real pathogen, your immune system is ready to fight it,” says Moss. In the case of the MMR or MMRV vaccine, that immune response to the vaccine may mean a rash or fever.

Fevers associated with viruses or, occasionally, vaccines, can cause febrile seizures. “They are certainly scary to parents”—a child may convulse or be unresponsive, usually for a couple of seconds or minutes—“but they are generally harmless,” Moss says. Crucially, “they do not cause long-term neurological damage, [and] they do not increase the child's risk of epilepsy or having a seizure disorder later in life. Children grow out of this, and hence the reason why the MMRV vaccine can be given at the second dose,” says Moss.

What the Change May Mean for Patients

Since most American families already opt for separate shots of MMR and varicella vaccines at the first dose, “they don’t need to do anything differently,” says Moss.

If a parent is concerned about the number of injections their child receives, “they might ask a pediatrician about the rationale” behind the two different options.

As for insurance coverage: ACIP has voted to halt MMRV coverage under the Vaccines For Children federal program, which covers vaccines for kids in low-income families.

For those privately insured, “the worst-case scenario would be that an insurer would not cover the MMRV vaccine for the first dose”—and the child would have two injections at that doctor’s visit instead of one.

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: