World Immunization Week: Preventing a Global Measles Outbreak

In the shadow of COVID-19, vaccination against other diseases faltered. Reduced immunity and more disease-susceptible people have set the stage for a global resurgence of the most contagious pathogen we know.

While the world’s attention was on the novel coronavirus, other viruses persisted. Now that COVID mitigation efforts have faded, those viruses are flourishing once again—with measles poised for global resurgence, says William Moss, MD, director of the International Vaccine Access Center.

In this Q&A, adapted from the April 26 episode of Public Health On Call, Moss speaks with Josh Sharfstein, MD, about how major setbacks in global vaccine coverage over the past few years have seeded the deadly threat of a measles resurgence. They discuss why this year’s World Immunization Week—themed The Big Catch-Up—is aimed at mobilizing countries to bring routine vaccine systems back online, and what needs to be done to get ahead of one of the world’s most infectious viruses.

Public Health On Call

This article was adapted from the April 26 episode of Public Health On Call Podcast.

What happens if somebody gets measles?

Measles is an infectious disease caused by measles virus. It’s largely characterized by fever and rash. People who get measles will develop a fever and a characteristic blotchy red rash that starts on the head and extends over the entire body.

In some situations, measles can cause complications. Measles can even cause death, largely by pneumonia—either from secondary bacterial infections or measles virus itself—or through diarrhea. There are neurologic complications of measles that can be very serious, as well as a number of other complications. Measles, for example, used to be one of the most common causes of blindness in the world.

And one of these neurologic complications can happen years afterwards.

Yes, that’s right. There are really three neurologic complications. There’s an autoimmune phenomenon that occurs early on called acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis. There’s another type of neurologic complication that occurs in immunocompromised patients where measles virus actually replicates in the brain. But the one that occurs eight to 10 years after measles cases, called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, is a progressive and fatal neurologic deterioration. It’s quite rare, but it is one of the most serious consequences of measles.

But we did get measles under control.

Before the introduction of the measles vaccine, which was first licensed in the U.S. in 1963, there were an estimated 2–4 million deaths per year globally due to measles. It was one of the major causes of child mortality.

Since then, we’ve seen remarkable progress in the reduction in measles cases and deaths as a result of the scale-up of measles vaccines. From 2000 to now, it is estimated that measles vaccines have prevented close to 60 million deaths.

But in 2019, we saw a global increase in the number of measles cases. There were particularly large outbreaks in Africa. Even here in the U.S., there were 1,274 measles cases reported, which was the largest number since the last big outbreak, from about 1989 to 1991. There were about 200,000 measles deaths globally in 2019.

Why did measles come surging back? Did the vaccine stop working?

No. Measles virus is highly contagious—much more contagious, for example, than SARS-CoV-2 or the influenza virus. In fact, it’s one of the most contagious pathogens we know of. Because of that, it requires very high levels of population immunity in order to decrease the number of cases, which requires very high levels of coverage with measles vaccines around the world.

Because we haven’t achieved those very high levels of immunization coverage, we have more susceptible individuals, and that allows for these large outbreaks. It’s not a problem with the vaccine, which is safe and highly effective. It’s that not enough people are getting vaccinated.

We know that a lot of vaccination rates fell around the world during the pandemic. What did you see for measles?

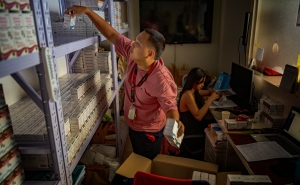

We saw two things happening. One was disruptions to routine immunization services—whether related to vaccine supply chain problems, problems with staffing in clinics, or, here in the U.S., parents not being able to bring their children to a health center or pediatrician to get vaccinated.

In many countries around the world, we conduct mass vaccination campaigns to try to make sure that enough children are vaccinated. During the pandemic, there were disruptions and delays to these campaigns.

All of that resulted in a lot of unvaccinated children and a decrease in measles vaccine coverage globally. Measles vaccine coverage around the world with the first dose had hovered around 85% [since 2015]. It dropped to 83% in 2020 and 81% in 2021. That’s the lowest measles vaccine coverage we’ve had globally since 2008. That may sound like a small percent decrease, but it translates to a large number of children: It’s now estimated that about 25 million children have missed out on measles vaccines globally. And that number increased from 2019 to 2021 by almost 6 million.

That means a large increase in the number of children susceptible to measles.

Yet measles cases decreased in 2020. Why?

This is what’s interesting: After May 2020, globally and in the U.S., the number of reported measles cases dropped to historically low levels.

There are several potential explanations for this. One is that there were just fewer susceptible people after the large increase in cases in 2019. Second, we know that surveillance systems were impacted by the pandemic, so some of it could be poor reporting or disrupted surveillance. I think the most important thing was that many of the measures put in place to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2—lockdowns, masking, less travel—reduced measles virus transmission, because it, too, is transmitted through the respiratory route.

If those theories are right, and there are a lot more susceptible kids, then we could see a pretty big surge in measles as we emerge from the pandemic.

That’s precisely my concern and the concern of many in global public health. Right now we’re seeing large numbers of cases in India, Ethiopia, Indonesia. The fire is burning in many countries in African and Asian regions that have poor health care systems, where there’s been a growing number of susceptible children. And that fire is going to spread. With more susceptible people and declining vaccination rates, we have a setting where we could see the forest fire spread around the world. We could be right at the beginning of large measles outbreaks.

What can be done to blunt the potential wave of measles cases and serious illnesses and deaths?

The bottom line is that we have to catch up on routine vaccinations. The last week of April is World Immunization Week, and the theme this year is The Big Catch-Up. It’s about getting the world’s immunization systems to recover from the setbacks of the pandemic and get back on track to meet our country, regional, and global goals. That’s what we need to do to prevent a large-scale global outbreak of measles.

Is the world mobilizing like it should?

We’re not there yet. I recognize that we’ve just been through three difficult years with this pandemic and struggling with maintaining high vaccination rates during COVID-19. But we really need to mobilize to prevent the resurgence of other vaccine-preventable diseases, or else we’re going to be seeing outbreaks—and measles is the one that’s going to come first.

Joshua Sharfstein, MD, is the vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement and a professor in Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is also the director of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and a host of the Public Health On Call podcast.

RELATED:

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: