A Prescription for PrEP Uptake

The public health community heralded the FDA’s 2012 approval of PrEP–pre-exposure prophylaxis–as the beginning of the end of the HIV epidemic. One pill a day can prevent HIV infection. Ten years later, many of those at risk for HIV never start taking PrEP, and the promise of the drug has yet to be fulfilled.

When the FDA approved the HIV prevention medication for pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, in 2012, the public health community heralded it as a turning point in the epidemic.

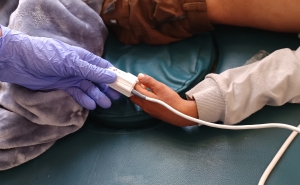

If followed correctly, a daily regimen of PrEP—one pill per day—decreases a person’s risk of becoming infected through sex by 99% and from injection drug use by at least 74%.

However, 10 years later, the promise of PrEP has yet to be fulfilled.

In 2020, fewer than 25% of the 1.2 million people who could benefit from PrEP received prescriptions, up from 3% in 2015. (The CDC recommends PrEP for those at high risk for HIV, including men who have sex with men, injection drug users, and heterosexuals who have high-risk exposure.) There are also pronounced racial disparities in PrEP uptake: Although HIV disproportionately affects Black and Latinx populations, they are far less likely to receive prescriptions than whites are, due in large part to lack of insurance coverage and health care access.

Stigma and limited awareness of PrEP are also key contributors to poor uptake of the drug.

It’s a massive lost opportunity, says social epidemiologist Lorraine Dean, ScD, an associate professor in Epidemiology who studies factors that influence PrEP use.

“We could prevent almost all of our cases of HIV. PrEP is almost 99% effective,” says Dean. “If we got everybody on PrEP who is at risk in a timely manner, we could essentially eliminate new HIV cases,” which numbered 34,800 in 2019.

In an effort to move toward that goal, the Biden administration’s FY 2023 budget includes $9.8 million in funding over 10 years for a national PrEP program to provide the drug at no cost to those who are uninsured and underinsured, increase access to PrEP for Medicaid recipients, and establish a network of community providers to expand access to PrEP in underserved areas.

“We have not been able to really mobilize a public health response to PrEP because public health can’t afford to do it,” said Amy Killelea, JD, an HIV policy expert, in a recent episode of Public Health On Call.

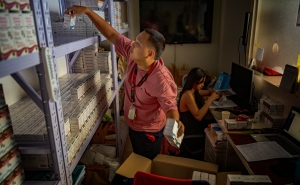

A key component of that response, for example, might mean making it easier for community health programs in underserved areas to work more closely with providers—perhaps making use of telehealth—who can prescribe PrEP.

“Telehealth is a great and underutilized way to ensure that you are actually reaching people where they are … people who are not walking into a primary care provider,” Killelea says.

Yet even when people are prescribed PrEP, there’s no guarantee that they will fill it, as Dean found in a recent study that looked at PrEP uptake from a novel angle. While many studies on PrEP have focused on what happens after a person picks up their first prescription, Dean wanted to know what was happening before that point: How many people with new PrEP prescriptions actually filled them?

The results, which documented “PrEP reversals”—that is, people who delay or don’t fill their prescription, leading the pharmacy to reverse the insurance claim for it—were “shocking,” says Dean, who with Amy Nunn, a professor at Brown University, led the research team.

Their analysis of pharmacy claims from 2015 to 2019 found that nearly one in five people with a new PrEP prescription delayed or never filled it. About 75% of this group still had not picked up their PrEP a year after receiving it, and 6% were diagnosed with HIV.

“What’s really painful is that among the people who weren’t picking up, there was about a three times higher risk of HIV,” says Dean. “This is HIV risk that is avoidable—clearly, clearly avoidable if we can get people to at least show up and get that initial prescription.”

Even when insurance covered the full cost of a PrEP prescription, 8% of people delayed or did not fill it. When it cost $10 per month, the rate of reversals was double. And paying for the prescription isn’t the only cost associated with PrEP—there are also required lab tests every three months to confirm HIV-negative status.

In a move to address cost barriers to obtaining PrEP, in 2019 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force gave PrEP an “A” rating, meaning that private insurers must cover PrEP and PrEP care services without co-pays or deductibles. Data is not yet available on the measure’s effectiveness.

Killelea describes Biden’s plan to create a national PrEP program as a chance for a “do-over,” 10 years after the drug’s introduction.

“The worry is that here we are at another blockbuster moment, and if we don’t do something different, we’re about to head down the same road,” she said.

Jackie Powder is the assistant editor of Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health magazine.