Contact Tracing on Campus: What Universities Should Know Before Bringing Students Back

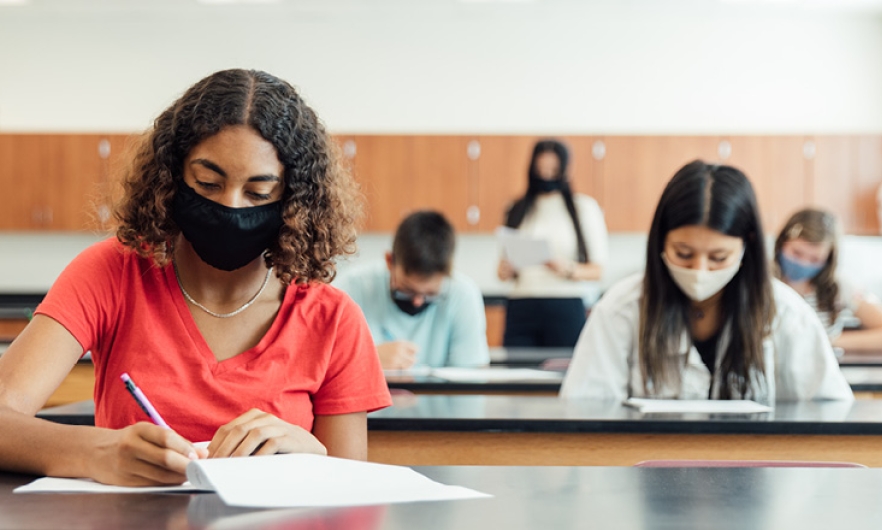

Campus life brings a risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Colleges need to have a plan to minimize risk--and to act when transmission occurs.

The first few weeks of August are normally when college students prepare for the fall semester.

But this year is different, and the word “normal” isn’t being used very often. Instead of excitedly awaiting their dorm assignments, many students are still waiting to hear whether they’ll return to campus, and if so, what that will actually look like during the coronavirus pandemic.

In this Q&A, adapted from The Chronicle of Higher Education’s Viral Vectors panel discussion on August 5, Emily Gurley, PhD ’12, MPH, and Tolbert Nyenswah, MPH ’12, discuss the importance of contact tracing on college campuses, and universities’ responsibilities to ensure the safety of their students, faculty, and staff.

If colleges are bringing students, faculty, and staff back on campus, should contact tracing be one of the school’s responsibilities?

EG: If colleges and universities are bringing people together where they’re going to have contact and create opportunities for transmission, then those officials should be in direct conversation with public health departments about how that’s going to work. University officials should, at the very least, be facilitating the process of contact tracing and linking resources with the local health department.

Contact tracing within a particular community is much easier when there’s a preexisting relationship with a degree of trust when communicating a message to that community. Colleges and universities have that relationship already with their students, faculty, and staff, so it would really be absurd for them not to be involved in the contact tracing process.

Additionally, the importance of their involvement is underscored by the fact that many students and faculty get their health care from their institutions. As people in that health care system test positive for the virus, there has to be a way to communicate those results and act on them.

Can the development of new digital contact tracing programs and software apps utilizing Bluetooth and other technology compliment the “old-fashioned” use of human contact tracers? Do those two fit together?

EG: Those technologies are aimed at helping to identify who may have been exposed using a variety of strategies. Contact tracing programs should consider all of the resources available to them in order to be effective, but they also need to be specific about what problem they’re trying to solve with which technology. It’s important that the program feel confident that the technology does not create larger problems than those they’re trying to solve.

There’s a special relationship between the staff and students at a university, so you can do things in that context that perhaps would not be as easy to do as with the general public. You can help facilitate contact tracing should someone become infected—and that's going to happen. You can do it in a very old-school way, just by knowing who goes to what class and whether they were in class that day.

At this point, there isn’t much data on how well tracing apps work, so universities, or any entity, would need to be aware of what types of contact they are actually capturing and how these data streams would be able to improve contact tracing.

The CDC considers close contacts to be people within six feet of infected individuals. Some experts say a person can be exposed to COVID-19 even if they're beyond that six-foot span. How should colleges respond with contact tracing work given that discrepancy?

EG: There are three types of contact: physical contact; close contact, which is defined as being within six feet for more than 15 minutes; and proximate contact, which is described as being more than six feet away, but within the same room for a prolonged period of time—more than an hour or two.

Folks who have contracted the coronavirus are most likely to infect the people they are closest to, such as the people they live with. There are some examples of transmission due to an infected individual being in the same room with other people, but it’s typically not across a very large lecture hall.

There’s no such thing as no risk. If you’re indoors without rapid airflow, then there is some risk for transmission. In these situations, physical distancing—which should always be the first thing you do—combined with face coverings can help reduce the risk.

How should colleges and universities determine what metrics would constitute a closure that would result in sending students home?

EG: It’s important for colleges to think about these metrics, or limits, before reopening so certain guidelines are set in place, rather than making decisions on the fly. Universities need to use the trust they have with students, faculty, and staff to determine what level of transmission on campus would make them no longer feel safe.

It’s also important to consider the burden on the health care system, both within and outside the university. Are you going to be able to provide care for those who are sick? In addition, the schools need to evaluate the capacity of their contact tracing program, as well as testing capacity. If you’re unable to meet needs for testing, medical care, isolation and quarantine, then you might consider closing down.

Again, it’s imperative to have these conversations before reopening.

TN: In order to have a safe reopening, you need to have protocols in place from the very beginning.

A major issue for the U.S. right now is testing. In order for schools to reopen safely, we have to have effective and timely test results. If it takes three to six days to receive results and the asymptomatic child is still going to school, then the virus will likely spread.

In West Africa during the Ebola outbreak, we had infection prevention and control measures in place—including what to do if someone tests positive, where to take them, how to test them, and how to deal with tracing those they’ve had contact with—before we reopened schools.

Emily Gurley is an associate scientist in Epidemiology at the Bloomberg School. Tolbert Nyenswah is a senior research associate in International Health at the Bloomberg School.